The Gotek USB floppy emulator, especially with the open firmware Flashfloppy has become a staple for many retro enthusiasts for upgrading old computer systems with a “modern” solution for loading software on the old systems. I am also one of these enthusiasts. As a retro system builder especially of the IBM-PC compatible kind, I am used to configuring these systems using jumpers. No “plug and play” feature here. The Gotek has also some jumpers you must set for using it on an IBM-PC. IBM-PCs make use of a cable that you can connect to two disk drives to one controller.

The selection of which drive is drive A: or drive B: is determined by the distinctive twist in the cable between the connector in the middle and the connector on one of the ends. If the drives you want to connect have jumper for setting the drive ID then both drives need to be set drive ID 0. This is especially the case for most 5 1/4 inch floppy drives, the later 3.5 inch disk drives often do not have drive ID jumpers and are set to ID0 by default.

The Gotek floppy emulator has also such a jumper S0 en S1 and this needs to be set to S0. However, there is another jumper JC on the Gotek, which in conjunction with the setting in the FF.cfg file (see highlighted code below the image) for flash-floppy to determine that the drive is in IBM-PC compatibility mode. I configured several Goteks in this way on my retro IBM-PC systems.

# Floppy-drive interface mode

# shugart: P2=DSKCHG, P34=RDY

# ibmpc: P2=unused, P34=DSKCHG

# ibmpc-hdout: P2=HD_OUT, P34=DSKCHG (not generally needed: prefer 'ibmpc')

# akai-s950: P2=HD_OUT, P34=RDY (Akai S950)

# amiga: P2=DSKCHG, P34=DRIVE_ID (not generally needed: prefer 'shugart')

# jc: JC closed: ibmpc, JC open: shugart

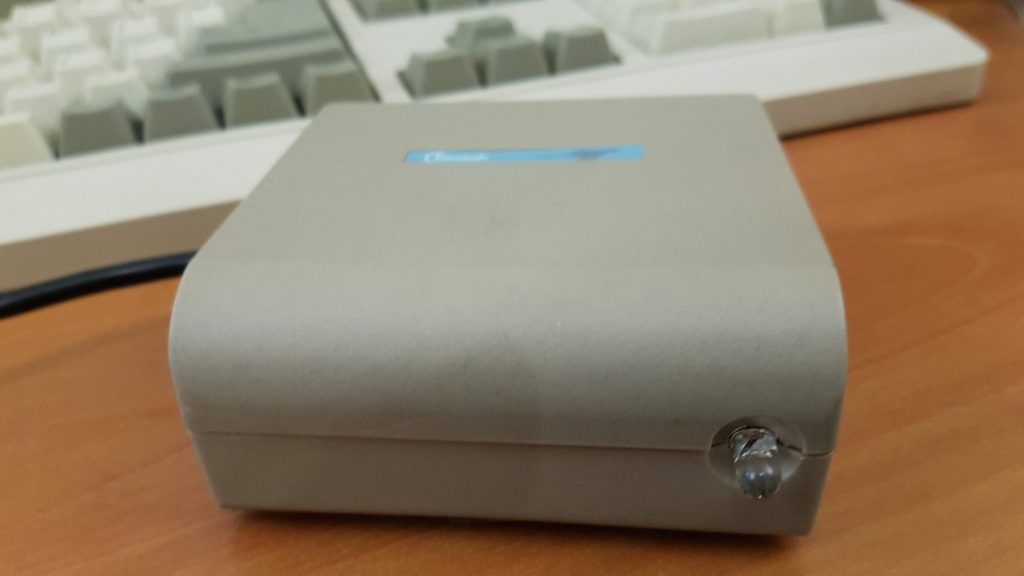

interface = jcSo having this presumed knowledge I got a new Gotek drive in and set the S0 en JC jumper and connected. But to my surprise, the drive did not work. Troubleshooting went from, checking the FF.cfg on the USB drive used, trying different locations on the cable, using a known working cable, checking with a known working Gotek and floppy drives, also in combination with the new Gotek at different positions on the cable, even reflashing the firmware and checking the disk controller. All to no avail. I even started thinking I was duped out of my money by a fake unit. So I started examining the board of the Gotek. I knew there were different incarnations of the thing, some versions best to be avoided. Then I noticed that the New Gotek was different from the previous working one.

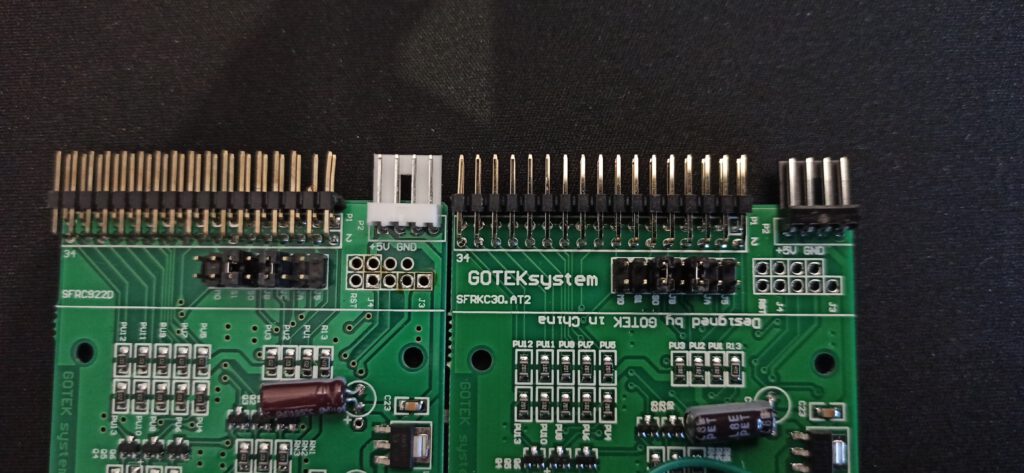

Gotek SFRKC30.AT2 has no JC jumper!!

The older Gotek I had laying around had as board number SFRC9220, the newer Gotek was labelled “GOTEKsystem” with board number SFRKC30.AT2. I was already reading through the Flashfloppy wiki to see what could cause the problem and was now looking for information on this particular iteration of the Gotek. In the Gotek compatibility section, some are listed and there I noticed this side note: “SFRKC30.AT2 (QFN32): Missing the original rotary-encoder header, but features the new KC30 rotary header. Also missing JC jumper location.”. A bit confused I looked back at the board and now noticed the JC label was missing from one of the 7 jumpers, but there was a jumper header. This jumper header is not functional, so even when bridged a Gotek SFRKC30.AT2 with USB stick having the interface=jc setting activated in the FF.cfg file, will think the drive is in shurgart mode not ibmpc mode. And voila, changing this setting in the FF.cfg file from settings=jc to settings=ibmpc made my new Gotek work flawlessly on my 286 build.

So to summarize, when using a Gotek with board SFRKC30.AT2 in an IBM PC compatible, you only have to set jumper S0 and make sure that the flashfloppy FF.cfg file has the interface parameter set to ibmpc and not jc.